Salon: The Nazi history of Hans Asperger proves we need a new word for this type of autism

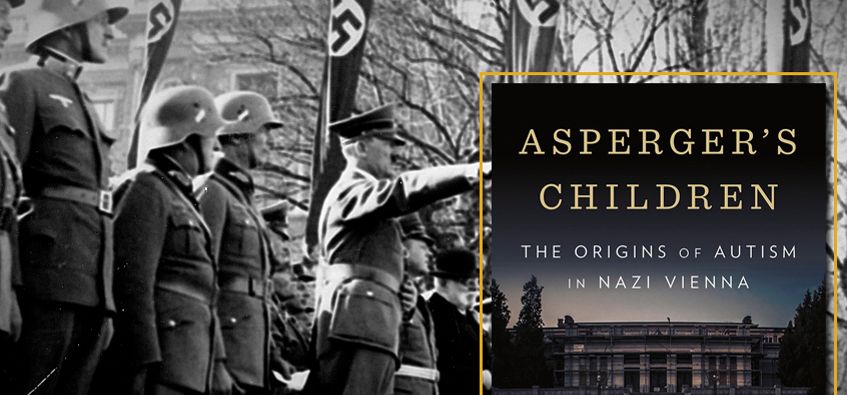

Back in 2012, the American Psychiatric Association voted to remove “Asperger Syndrome” as an official diagnosis in their manual. Their decision was based on terminological precision rather than ethical considerations; they felt that it ought to be folded into autism spectrum disorders and argued that merging it with the broader spectrum would “help more accurately and consistently diagnose children with autism.” Nevertheless, as Edith Sheffer’s new book “Asperger’s Children: The Origins of Autism in Nazi Vienna” points out, they wound up being ahead of the curve when it came to disassociating the condition itself from the name of Hans Asperger himself.

Back in 2012, the American Psychiatric Association voted to remove “Asperger Syndrome” as an official diagnosis in their manual. Their decision was based on terminological precision rather than ethical considerations; they felt that it ought to be folded into autism spectrum disorders and argued that merging it with the broader spectrum would “help more accurately and consistently diagnose children with autism.” Nevertheless, as Edith Sheffer’s new book “Asperger’s Children: The Origins of Autism in Nazi Vienna” points out, they wound up being ahead of the curve when it came to disassociating the condition itself from the name of Hans Asperger himself.

As Sheffer meticulously documents and proves in her book, Asperger collaborated with Nazi Germany in unforgivable ways. He gave public credence to their most toxic views on race and biology (known as eugenics), served as a medical consultant for Adolf Hitler’s administration and recommended that countless children be put to death at the Spiegelgrund, a clinic for “inferior” children. Many of Asperger’s career opportunities were given to him because of the racial privileges he was afforded in Nazi Germany, and although a narrative later emerged that depicted Asperger as an opponent of Nazism, the historical evidence demonstrates that he both sympathized with aspects of and personally benefited from Nazi ideology.